miércoles 31 de agosto de 2011

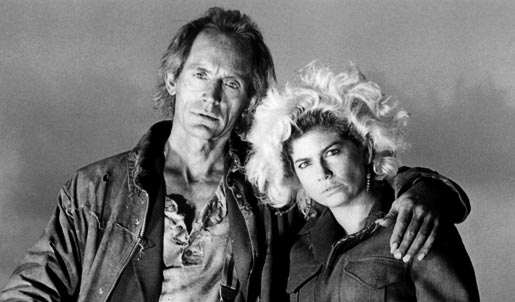

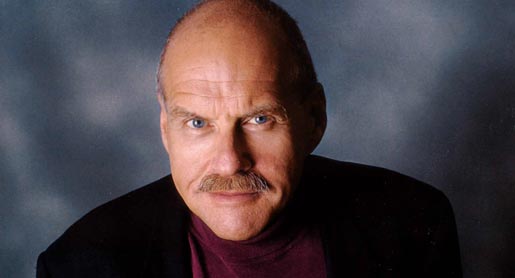

Dean Gorissen is an Australian illustrator and designer. His editorial work has appeared in a variety of newspapers and magazines; Child, Australian Family Physician, American Lawyer, Sunday Life Magazine and The Big Issue among them. Furthermore, he has designed cartoon characters for TV series like Deadly, and as well as other books, Dean has illustrated Matt Zurbo’s I Got a Rocket!, My Dad’s a Wrestler and Ten Little Elvi. This year he saw published his first book as a writer/illustrator: The Search for Bigfoot Bradley. Some of his most recent and personal work was done for the six-book series Long Story Shorts, published in Australia by Affirm Press. His subdued but striking covers for this project compelled me to chat with him about his designing process. You can learn more about Dean at his site.

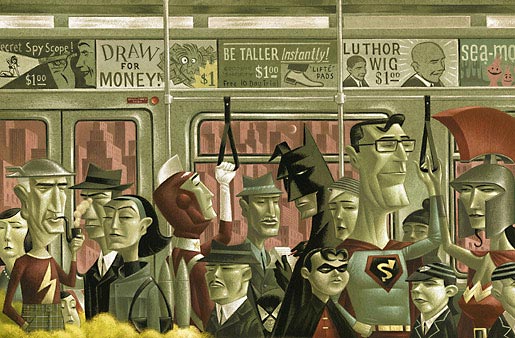

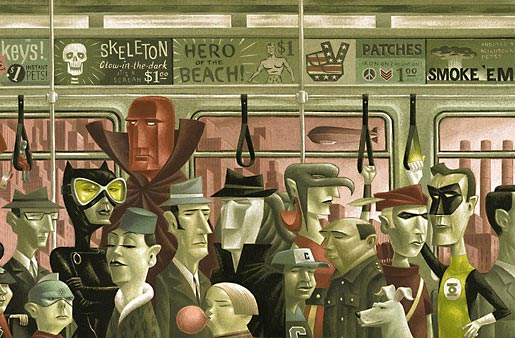

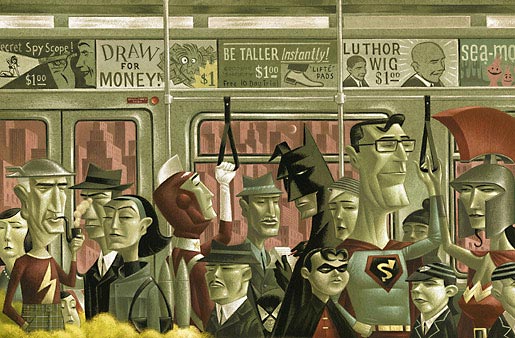

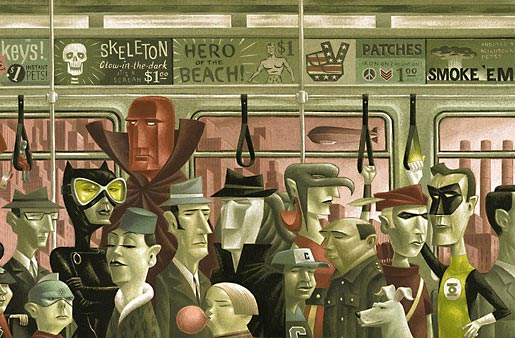

Both this image and the precedent are details from Supertrain, a personal piece

about the saturation of superheroes in contemporary popular culture.

Oscar Palmer: I’m assuming you knew beforehand that this was going to be a collection of six books, so what I’d like to know is: did you plan an overall design for the collection right from the start or you just had some general ideas which you then applied accordingly to each and one of the books?

Dean Gorissen: The series was always planned to be six books. Martin Hughes, Publisher at Affirm Press, certainly wanted an overall link for the series, but I don’t think either of us quite knew what that would be at the beginning. It was a big leap of faith on his part, really. I’d done a number of editorial illustrations for Martin a few years before, when he was editor of The Big Issue Australia, but generally figurative stuff, painted. Stylistically nothing like the book series. Actually, come to think of it, he originally rang up to ask if I knew of anyone who might be suitable! I didn’t get any direct design guidelines at all but we did discuss it a lot, more for the emotional note we wanted to hit. I think the only thing Martin was sure of early on was that he didn’t want to have a series logo for «Long Story Shorts» on the cover, back or front.

We were really trying to find a balance between each book being able to stand alone, retaining its own integrity, while clearly being part of a series with an overall cohesive aesthetic. Whether that was typographically, thematically or stylistically was up in the air. Early on, after reading one story of the first manuscript, I’d thought of the series as maybe in very different illustrative styles, but with a cohesive typographical and design approach, which Martin was open to. So I approached it in the usual way, conceptual scribbles, roughs, got the paints out, even started playing with photo montage and manipulation. But as soon as I’d done a first draft of the first cover it didn’t take long to realise it would set a precedent that would trap the whole series. So I threw the whole approach out, which was heartily endorsed and encouraged by Martin, and started again. It took a bit of an attitudinal shift to really get onto it. I realised I’d approached it solely as an illustrator, focusing on one aspect, and that I really needed to view it as a designer. Affirm sent the full manuscript of the first book, Under Stones and I just immersed myself in it. Once I connected with it emotionally and intellectually, the tone just presented itself and I started to get a sense of the series as a whole. I drafted up a template for the other cover elements, front and back and set some type parameters for title and author, then just sat down without roughs or scribbles, just some thoughts and a mouse, did it in a fairly intense burst and sent it off to Martin and series editor Rebecca Starford. The response was overwhelmingly positive and personally I was bursting with excitement to do the next one. I chose different fonts for each book title, again trying to enhance each books individual identity, but there’s an overall typographical similarity in terms of weight, spacing and size. And on each spine is a letter that on completion of the series lines up to spell out ‘shorts’. Which sounds kind of gimmicky, but works a treat for a sense of completion without overwhelming the thing. We were really keen to give the series a sense of it being a crafted, encapsulated series that was a bit of an event, something to value, a bit of a collectors item.

Tangled, editorial for article on inefficiencies in the health system.

OP: For all these covers you somewhat departed from your usually recognizable style, renouncing to your trademark «cartoony figurativism» (so to speak) and dealing instead mostly with objects, even getting close to abstract forms. Why and how did you choose this particular style for this particular collection? Did you think maybe the less figurative the more evocative the covers would be?

DG: «Cartoony figurativism», that’s perfect, I wondered what it was called! There were a number of factors in play at the time. I was restless as an illustrator, feeling stale, and a bit stylistically straight jacketed. As an illustrator there’s often (or maybe I just think there is) a certain pressure to be a known quantity by the marketplace. I totally understand why, but it was feeling increasingly limiting. My wife and I have a small design studio, Room 44, and I’d begun doing the odd design job here and there. So from a personal point of view, I’d been longing for a project like this for a while, something that offered the opportunity to transcend the usual stuff and craft a whole series as a designer as well as illustrator. Where you could evaluate the job from a different point of view and trust your own instincts and drive the thing more. So I suppose I chose the style because it felt right and I could. Being overly figurative just seemed as if it would spell out the emotional reaction a viewer is supposed to have, not leave any room for a potential purchaser to be engaged or intrigued. It was incredibly liberating actually.

Once I’d established a tone and approach with the first one, I just set a rule that I would do no roughs, just read the manuscripts, post, make a few notes and just go straight to the cover templates and start drawing, with a mouse, not stylus. So there’s no sketches anywhere, just the odd scrawl or note on a manuscript to remind me of a thought.

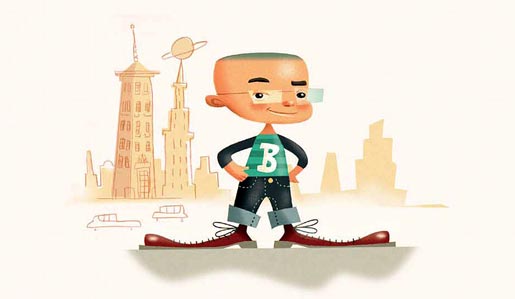

Bigfoot Bradley is the main character from Dean’s new book.

OP: I’m guessing that, with these covers, you didn’t choose to illustrate specific passages from the books, but rather to convey a particular mood. For instance, I don’t know if there’s actually a bike in Nineteen Seventysomething, but your illustration sums up beautifully that feeling of old days and times past. Do you think is better and more effective to be evocative (that word again!) than purely illustrative?

DG: I don’t have a general rule for anything really. I try to approach any assignment on it’s own inherent character. It just seemed that a basically visceral response was the right way to go, reducing elements to symbols give the reader some credit and leaving interpretation open to some degree. You’re right, there’s no literal visualising of specific passages, though there’s a couple that are inspired by certain scenes. And sometimes talking with the author, helped shape things too. All I know for sure is that in order to do them honestly, I needed to read the books and so it was the books both individually and as a series that basically defined the response.

Click for bigger versions.

OP: Could you elaborate a bit the thinking that went behind each one of the covers? How did you get to the final images? Let’s start with Under Stones.

DG: Under Stones contains a passage that inspired the cover image, though it’s not a literal representation. Under Stones was written by Bob Franklin, an actor and stand up comedian, and though there was often something intimidating about Bob’s stage persona, his book is sort of borderline horror, not in a blood soaked way at all, but in it’s unsettling/ghastly/dread revelations about seemingly ordinary people. It really creeps up and scares the crap out of you. Martin had described it as «sort of horror lite» and later, when reading the first story, well into it, I’m thinking, «what was he talking about? Yes it’s involving, personal, gets under your skin, but… Ohhh, ohhhmigod!». So it was important to visualise that feeling and create some intrigue to try and see what was under those stones. There’s a scene in some wetlands in the book that just sends chills. It was full of a sense of unknown and ancient wrongs, the stuff that’s buried at the heart of colonial cultures, and I wanted to capture that in some way, and wanted the drawing style to nod to it, too. This was the first book in the series and (after the false start of the first attempt) it came very quickly, really in a bit of a torrent after reading the book. If I could liken it to anything it was almost the stream of consciousness you get when fully immersed in writing something. I don’t think it changed substantially from that, though I think I did a version with the sky predominantly white.

OP: And Nineteen Seventysomething?

DG: That cover grew out of a long telephone chat with author Barry Divola. We’re the same age, grew up in the 70’s, and so much of what he wrote made me laugh in recognition. We sort of bonded over that iconic bike, the dragster, and the experience of the suburbs. And I put stuff in there for me, too, like that barely visible flying saucer top right, because I can remember often waiting and hoping one would arrive and just take me away! A very different book to Bob’s and so the approach was much gentler. It’s nostalgic, without wearing rose coloured glasses. Stylistically, I was heavily under the influence of the curved geometric wallpaper I remembered from our lounge room! I did a couple of takes on this to get the tone right.

Click for bigger versions.

OP: Speaking of tone, Known Unknowns by Emmett Stinson has one of the moodiest covers I’ve seen in a long time.

DG: Thanks! That cover really comes from the book as a whole. Not only is it definitely post 9-11, but there’s a kind of inevitable disintegration that pervades. It’s lonely. And the smoke theme recurres throughout, whether it’s cigarettes, a joint, a barbeque or a car exhaust. I don’t know if that was deliberate on Emmett’s part or not, but I read it in one sitting, and drew it. I just knew what it was going to be, and once I got satisfied with the shape of the smoke/flag device it basically drew itself. I don’t remember having any internal questions about it. I just felt like a vessel for it. I’m not sure if I’m remembering this right, but think Martin was a bit unsure about it, or was concerned from a shelf point of view that the palette was too dark, something like that. I felt very strongly, though, that it was right.

OP: Having Cried Wolf.

DG: Gretchen Shirm’s book is all about interconnected lives, stories that intertwine often lightly but very definitely, revolving around a small coastal town. Initially I really had to rush with this one. If I remember right, we needed to get a cover out in a couple of days to book a spot in the publishing cycle. Read it, too quickly, and I wasn’t satisfied with how I was filtering it. I’d basically expedited an information input instead of reading it. Anyway, I overcompensated for my uncertainty by producing a whole bunch of options that were okay, but fundamentally as expedited as my reading had been. I couldn’t let it lie, though, so after some begging from me and wheedling from Martin we ended up getting an extension, I could read the book properly, felt it and found its voice. The sense of detail, and a really multi-layered reality is astounding. Gretchen, I found out a month or so later, is relatively young, only 30 when the book was completed and I remember being pretty stunned that someone of that age could have such an innate understanding of how lives can play out, the journey of long term relationships, emotional implications, consequences, actions and reactions that reverberate through a family or community and the unresolved nature of our lives.

|

|

|

Click for bigger versions.

OP: I think Bearings by Leah Swan was next?

DG: Yeah, that was easily the quickest cover out of the whole series. It was just one of those perfect moments. The manuscript arrived, the deadline was close but not too close, read it over a couple of nights, sat down one morning and drew. It’s very powerful work, the book, and really is about storm tossed lives, both metaphorically as well as environmentally. Like Emmett’s, there was really no question in my mind about it. The paramount thing to me was, I wanted to feel those waves. I was immensely satisfied with it, and the reaction at Affirm was immediately positive.

OP: And what about the final book in the series, Irma Gold’s Two Steps Forward?

DG: Two Steps Forward is very much about difficult, often heartbreakingly sad lives, but with a resolute core to find some kind of happiness or kindness. The reaction from Martin and Rebecca was again quite immediate: they hated it a lot. Which I was kind taken aback by. But they were right. I’d missed the core of it. After Martin and Rebecca’s initial reaction to my first attempt, like always they gave me ample opportunity to sell them on it or defend it, and I was unable to with any real conviction. Always a sure sign that I don’t really believe in something! Martin suggested I go back and reread it. Often the stories concern children, the fractured relations between children and parents, especially when circumstances change. And how we deal with the tragedies of life, the pain of loss. I got real sense that the adults in the book were very much still children, like we all are, stumbling and unsure, seeking comfort even when none is in sight, learning and growing. It’s often unbearably sad and at the same time beautifully uplifting. So even though I needed to stick to the subdued tones, flat colours, I wanted to counterpoint that with these childhood sketches, stretching across the landscape, moving toward something unseen.

|

|

|

A couple of Dean’s illustrations for Australian Family Physician. Click for bigger versions.

OP: Having designed and illustrated these covers all by yourself, and having illustrated in the past for other designers, could you elaborate a bit on the pros and cons of working alone on such a project?

DG: I can’t think of any cons. It’s all pros. Except it never felt that I was working alone. Absolutely I felt responsible for the visual approach of the series, but having direct communication with decision makers who both have a commitment and connection with the work beyond it being a bureaucratic assignment and who have a faith in your ability is a rare thing, and was really the key to the whole thing. And that trust allows some flexibility too. It lets you get it wrong sometimes, and pushes you to do it better without being in any way proscriptive and it lets you defend the solutions that you believe in passionately. There weren’t any other levels adding this or subtracting that, running it by multiple departments for approval or ticking this or that box and ultimately sucking the life out of it. Martin and I spoke a lot, and would exchange thoughts often robustly, but always to the ultimate betterment of the work.

OP: It’s funny, but with book design having become so sadly standarized and so imagebank-dependant (here in Europe at least), the first thing that came into my mind after seeing your covers for Affirm Press was not the work of other book designers but that of sleeve designers like Jim Flora and the recently departed Alex Steinweiss; not as retro pastiche but really as a contemporary evolution of that kind of design they pionereed.

DG: That is so not misguided! I absolutely aspire to their example. Both Steinweiss and Flora seemed not only to have a fidelity to the eccentricities of each task, but the ability to emotionally attune themselves to it too. I love the sophistication and elegance of Alex Steinweiss, and I‘m drawn to Jim Flora in particular, because while he could be abstractedly evocative (that word again!) he could really cut loose with some beautifully cool cartoony stuff that just burst with energy and enthusiasm, and all without losing what was essentially ‘him’. It’s an honour to be mentioned in the same paragraph.

Interviews

Cover Design, Dean Gorissen, Illustration Sin comentarios

jueves 18 de agosto de 2011

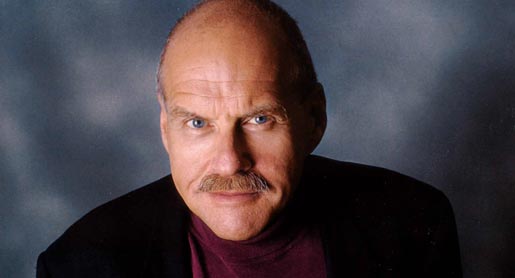

2011 is turning to be a very busy year for Lawrence Block. He brought back Matthew Scudder last May in the brilliant A Drop of the Hard Stuff (Mulholland Books) and next month we’ll be able to put our grubby paws on yet another new book of his: Getting Off (Hard Case Crime). Also, he’s writing a consistently funny and really informative blog, he has released almost all of his backlist as unexpensive eBooks and even joined Twitter. As an avid fan of his fiction I had been looking for quite some time for an excuse to chat with him; now I had three. No more delays, then. I’d like to extend my gratefulness to Mr. Block for his availability and generosity.

Oscar Palmer: Your career sprang from the “Write-for-your-Life” school of the digests and paperbacks, so I’m curious as to how do you see this new era of college courses, literary academies and «How To» manuals (some of which you’ve even authored) as opposed to the world in which you started your career?

Lawrence Block: Well, I feel conflicted. On the one hand, I’ve only read two or three instruction books on writing in my life, and they were all well over fifty year ago. On the other hand, I wrote a monthly column on fiction writing for fourteen years, and have published six books on the subject. I have to believe they’re of some value, yet I certainly made do without them, or their equivalent. And my own background has made me suspicious of MFA graduate programs in writing; I don’t know that they do any harm, but neither am I convinced they do much good, and I think the real danger leads in young people’s belief that they’re necessary. They prepare you to teach writing, but I don’t know that they prepare you to do it. I think one prepares oneself. I came of age when low-level magazine and paperback markets provided a good apprenticeship for writers. I don’t know if there’s an equivalent nowadays, but there may be. I think the Internet and possibilities for self-publishing may constitute a real game-changer. It’s far too early to tell what it may all amount to.

OP: You wrote a great post on your blog about your experience reading John Locke’s How I Sold 1 Million eBooks in 5 Months and how it led you to launch your blog and your twitter account. Also, your use of the Internet as a tool of promoting not just new work but giving a new life to your backlist in the form of eBooks is nothing short of exemplary. How many hours do you usually spend now on cultivating that direct relationship with readers, and in which ways have you altered your work routines to accommodate these new commitments?

LB: Well, I don’t time it. I sit for hours on end at my computer, and I switch from task to task, and lately I use the social media a lot, but I don’t think I’d do it if I didn’t enjoy it. This kind of dialogue with readers is just a different form of what I do in my books, you know. As is this interview. And I should add that I think all of this is counterproductive for those writers who don’t enjoy doing it. If I didn’t get a kick out of this, I’d be doing myself more harm than good.

OP: So, is it working? Have you perceived some renewed interest in your oldest work? Are you satisfied with how things are coming along since you entered the eBook market?

LB: Books of mine that were out of print forever have a new life as eBooks, and people are buying them and reading them and evidently getting some enjoyment out of them. How much that’s going to amount to financially is unknowable at this stage, and it may not really be the point. I’ve always believed that, if people read my books, I’ll make a living. Ultimately, you know, it’s the work that matters. I see writers who network and promote themselves like crazy, but they write books that nobody much wants to read, and while they may get people to try one, they’re not going to build anything lasting that way.

OP: A Drop of the Hard Stuff is your 17th Matthew Scudder novel. Seeing now how the character has evolved and gotten old and changed along the years, what would you say to a new reader of yours in terms of what to expect, not just of this particular novel, but of all the Scudder series?

LB: I probably wouldn’t say anything to the reader, preferring to let the books speak for themselves. As for Scudder’s aging and changing, I never expected that when I began writing about him. Fictional detectives generally stayed the same and never grew older. But the level of realism in the books was such that I felt I had no choice but to let Scudder grow and evolve and age, and I’ve never regretted this decision. The result has been that it may be close to time to stop writing about him, but if he hadn’t evolved I’m sure I’d have stopped long ago.

OP: The hiatus between your previous Scudder novel, All the Flowers Are Dying and A Drop of the Hard Stuff has been the longest between books since you started writing the character. Why it took you so long to get back to him?

LB: Hard to answer. Just as I rarely know what I’m going to write next, neither do I know why I write what I do. In this instance, I thought I was probably through writing the character. Then I thought of the particular premise of the new book, and its setting in an earlier and previously unexamined period of his life, and I was able to write it.

OP: A Drop of the Hard Stuff shares a title with a Dubliners album; When the Sacred Ginmill Closes was named after a line in a Dave Van Ronk song… How important is music to you?

LB: Actually, I don’t know how much of a role music plays. It may have played a larger one in the past than it does now. I don’t listen to anything while I’m working. The last thing I want is distraction.

OP: I’ve loved all of your Hard Case Crime reprints, particularly Grifter’s Game, The Girl With the Long Green Heart and Lucky at Cards, because in them you describe the mechanics of whatever the characters are doing in a way that puts to shame a lot of modern fiction authors, who tend to tell us how great their characters are instead of showing it with actions. Do you research a lot or it’s just that you’re damned convincing?

LB: I don’t do much research. I like to get things right, and the easiest way to do that is to use setting and milieus with which I already have some familiarity.

OP: Your new book, Getting Off: A Novel of Sex & Violence, makes it abundantly clear right up from the cover that this isn’t a Scudder or a light-hearted caper or whatever, and that’s because you received some backlash for some of the content in Small Town, which made me wonder: after more than 50 and very different books, there’s still people who have preconceived notions about how a Lawrence Block book should be, and they get mad about it?

LB: Good question. A lot of my readers seem willing to follow me whatever direction I take, but some have strong preferences. Some like the lighter books, others the darker ones. My feeling is that if I just write what I want to write, if I strive simply to please myself, it’ll work out all right.

Authors • Interviews

Hard Case Crime, Lawrence Block, Noir Sin comentarios

lunes 7 de marzo de 2011

Megan Abbott. Photo by Joshua Gaylord.

Universally hailed as a great stylist and rightful heiress to the greatest masters of hardboiled fiction, Megan Abbott has quickly become one of the most appreciated writers of her generation, deservedly so. And I’m confident that her next novel, The End of Everything (to be released July 7 by Little, Brown), will win her a much broader audience yet, far beyond the limits of noir aficionados already enthralled by her prose. Although there’s no shortage of good interviews with Megan available on the Web, I had a chat recently with her a propos of the Spanish release of her Edgar winner novel, Queenpin, so I thought I’d share it with you.

Oscar Palmer: When and how did you become interested in noir? I’ve read in your blog that you remember seeing Gilda with 9 or 10 years, so I’m guessing this is something that started brewing at a young age. Were your parent fans? Was this encouraged?

Megan Abbott: My parents were fans and very encouraging. They would scour used book stores for me for old movie books and take me to any revival screenings. Everything I write I can trace back to the old movies I watched on TV on Saturday and Sunday mornings. First, it was gangster movies—Public Enemy, especially—and then onto Howard Hawks, Billy Wilder. Somehow, those movies, especially film noir, became the dark foundation for me—they formed the world I wanted to enter, and writing was my way of entering that world.

OP: You’re obviously a great film buff, and I was wondering if you could elaborate a bit about how you think film has permeated your understanding, your expectations and maybe even your literary conception of what noir is. Or should be.

MA: Ah, that’s interesting. It’s true, my first exposure to noir was through film, and only fiction thereafter. For instance, I must have seen Double Indemnity a half-dozen times before I read it, in my 20s. I find them to occupy, generally, separate noir universes and I like to draw from both. There is something very special about the visual resonances film can give noir—bringing to vivid life these shadowy worlds, imparting a glamorous sheen that can make everything seem shinier, more hypnotic, more dangerous. The books, on the other hand, are so much more intimate and the use of first-person in particular (e.g., in Cain, Chandler) brings such intensity, makes everything feel rawer, closer. And, given the Production Code, the books also bring you far closer to the lurid, the unsayable. So these are two different worlds that speak to each other, whisper to each other. I love them both.

|

|

|

Queenpin around the world. Spanish edition (cover by Fernando Vicente) and French.

OP: Your first book, The Street Was Mine, was a scholarly essay on noir. Was this something you thought you should do before writing a novel, like a springboard or a laying of the grounds for your own novels?

MA: The Street Was Mine began as my graduate thesis. I had completed my Ph.D. coursework in English and American literature and I wanted to pick something different for my dissertation and I thought I might pursue all those wonderful books that became the basis of my favorite films. I read The Big Sleep and The Postman Always Rings Twice and knew I’d found my passion. I never had any intention of writing fiction, but while working on my thesis, I just needed some non-analytical outlet and found myself writing the pieces of what would become Die a Little, my first book. At first, it was just scraps, a vague idea, but the more I read, the more it fueled it. In writing a critical study, you don’t have as much opportunity to “enjoy your enjoyment” of the books you’re studying, so writing the novel was my way of doing that.

OP: I don’t know if you’ll agree, but I see your novels as some kind of answer to those Chandler and Cain classics you dissected in The Street Was Mine. Not as an antagonistic answer, but more of a parallel approach. Your characters inhabit that same world, but obviously they have a different way of dealing and a different point of view about what’s happening. Anyway, what I wanted to ask is; what did you learn writing The Street Was Mine and what impact did that have in your own prose?

MA: Thank you! I was aware, writing it, that these books were heavily a world of men, and there did seem a ripe opportunity to write these kinds of books with female characters who were not femme fatales (or not viewed as femme fatales and defined solely by their ability to entrap men). So I think that gave me a way in. But primarily reading all these wonderful books just made me want to be a part of their dark fabric. And reading so many in a row, the prose styles, the Manichean logic, the confessional qualities—it just enthralled me and I wanted to try to write like that.

He never saw it coming. Cecil Kellaway, John Garfield, and Lana Turner in

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946).

OP: Die a Little and Queenpin are set in the 50s. The Song is You in 1949. With Bury Me Deep you went back to the 30s. How big a part of writing these novels went to research? Also, I’m amazed at the seemingly effortless way you have of writing credible vintage dialog and slang. I know authors like David Peace listen to a lot of music, both good and bad, from the time they set their novels on, just to get a sense of which words were used and in which ways, among other things. What kind of sources do you turn to whenever you’re writing a period piece?

MA: I really love research—especially of the less traditional variety. While I will read standard history books, I prefer the more tossed-aside ephemera of the time, which I think can say a lot more about the culture than the so-called “official history.” I’m always trawling flea markets and yard sales for old cookbooks, catalogs, cocktail menus, cocktail napkins, lots of popular magazines and tabloids. Music too—that makes so much sense to me, David Peace’s approach. I listen to a lot of tossaway music, lost jukebox tunes, tin pan alley, novelty songs. I keep absorbing all of it until it becomes this sort of endless collage unfurling in my head. And then I stop, and start writing.

OP: You’ve used characters based on real women in other novels. Was there also any real life inspiration behind the character of Gloria Denton. Have there been, to the best of your knowledge, any real queenpins?

MA: Very few on the kind of scale Gloria works. Gloria is loosely based on Virginia Hill, the paramour of gangster Bugsy Siegel, the one after whom he named the Flamingo Hotel. I learned she was much more than a moll. The mob trusted her to move money and jewels, to go to Switzerland to open bank accounts. She had tremendous power. In 1951, she was called to testify in front of the U.S. Senate and she didn’t give an inch. She told them she didn’t know a thing about organized crime and insisted, “I work where I want and when I want. I don’t dance for nobody.” That line was intoxicating to me. I knew I wanted to bring a character like that to the center. Hill, however, appears to have been a pretty reckless person, and I wanted to make Gloria far more ordered, controlled. In that way, she derives more from, say, film performances of Joan Crawford, or Angelica Huston in The Grifters.

|

|

|

Left: The Damned Don’t Cry, in which Joan Crawford played a moll

modeled after the real life Virginia Hill (right).

OP: There have always been female mystery writers, but would you agree that we’re finally seeing an ongoing reinvention of the most male-oriented aspects of the genre, like hardboiled and vengeance yarns, being done by writers such as Christa Faust, Vicki Hendricks and yourself?

MA: I do think we are witnessing a real flood of tougher, darker crime fiction by women and it’s exciting to see it take on a kind of momentum. Of course, it’s been a help in terms of finding readers to be a woman writing in a traditionally male corner of the genre. You stand out. You’re an anomaly. And there’s also fresher terrain in terms of plots. There are still remarkably few noir novels about nurses or female school teachers, for instance!

OP: Name your three favorite film noirs.

MA: Oh, so hard. Today, I go with Double Indemnity, In a Lonely Place and Kiss Me Deadly.

OP: And your three favorite noir novels?

MA: The Long Goodbye, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, and The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Bogart and the always amazing Goria Grahame find themselves In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950).

Authors • Interviews

Es Pop Ediciones, Megan Abbott, Queenpin Sin comentarios

domingo 25 de abril de 2010

Todd Grimson’s Stainless, one of the best and more unjustly ignored vampire novels ever written, is something of a cult classic that still pops up regularly in blogs and message boards whenever a new reader gets ahold of a copy and gets blown away by its sheer intensity and its raw and bloody romanticism. I recently interviewed Todd à propos of the Spanish release of his novel; finding an interview with him it’s almost impossible even on the Web, so I thought I should post it here in English. Hope somebody enjoys it.

Left: English Cover. Right: Spanish Cover.

Oscar Palmer: It’s been thirteen years since Stainless was originally published. How do you perceive the changes experimented by American pop culture since then, and how do you think Stainless stands against this last wave of defanged and desexed vampires?

Todd Grimson: I haven’t watched any of the new vampire fare. So maybe it’s better than I think. Though not from what I hear. I thought to myself at the time that Stainless basically ended the genre, that it was the last and the greatest vampire novel ever. It sounds absurd, but I don’t mind sounding absurd.

OP: There’s vampires in Stainless and zombies in Brand New Cherry Flavor. What did using both of these pop horror icons allowed you as a writer?

TG: I started out (BNCF was written first) trying to organize what I accomplished sometimes in my short fiction… trying to work the “waking dream” quality I thought I occasionally achieved… into the longer form. I developed the idea of what I then saw as “cinematic realism.” This has an obvious relation to “magical realism” – at its most basic, you might call it Life + Special Effects. Given that our modern imaginations have been so infected by the language and vocabulary of film, and that my own dreams are vivid and cinematic, this all seemed to make sense. Stainless originated in a dream; as I worked on the novel the original vision was reinforced by other dreams making use of the images obsessing me by then.

Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest.

OP: Were you deliberately attempting to redefine or deepen vampire lore, or was this just a mean to an end, a good way of giving an edge to what could have otherwise been a simple love story?

TG: I wanted to write the Final, Ultimate Vampire Novel. I read all that was out there, brooded for a month. Anne Rice in Interview With a Vampire has three vampires living in early 19th century New Orleans, each supposedly killing one person each – every night. That’s over a thousand corpses a year when the population of that city was much less than today. And no one notices?! I thought this was ridiculous, and, worse than ridiculous, uninteresting. How much blood would one need per day? I have worked in a surgical intensive care unit, I was and am intimately familiar with blood and death. What if the vampire avoided the obvious bitemark on the throat, possessed some mild hypnotic power, was not as strong as a superhero, and only took enough blood to live? Say a bowl of soup’s worth? The bitten would most often survive. I discussed the possible issues with a physician I knew. There is a medical condition which requires frequent transfusions, another in which a patient may be hypersensitive to the ultraviolet light of the sun. It’s been postulated that the accumulation of “heavy water” in the body is what causes aging and eventual death, Maybe a disease might have a side-effect which is positive, perhaps something offbeat in the spleen or the thyroid reregulating the organism? It’s not completely impossible. It may not be likely, but for my purposes such hypotheses at least moved us closer to something real. There is minimal if any invocation of supernatural power in this book. Justine can be killed. And you do not instantaneously die when her teeth touch your neck. Rattlesnake venom is not even so fast as that.

OP: You use quite a lot of characters and situations for such a short novel, creating almost a mosaic of narratives. Some of them, like the fifties episode with the police detective or the shooting of the vampire movie in 1969 almost seem like complete short stories. Was this hard to manage without losing sight of the main storyline? And was this fragmentation always part of your original plan or did it grow as you went along?

TG: I didn’t want Justine to have 400 year old eyes. There’s no vulnerability in that, no capacity for some survival of the child within. Justine is fragile in some ways, and this also makes her more sexy. She suffers from some amnesia. The past is like a dream. It’s also important that she believes in God. When you believe in God you experience it much more acutely if you come to believe you are damned. The flashback scenes showed us to some extent a different Justine. I mimicked the language and mood of Poe, then for 1950s Los Angeles I used some heightened notion of the James Ellroy one finds in The Black Dahlia. The 1960s scene is the Pynchon of V. and my memories of such films as The Trip — gone cruel.

Bertrand Tavernier’s The Passion of Beatrice, starring Julie Delpy.

OP: Your writing in Stainless is very sparse but oddly poetic. Did you have to labour a lot to get this balance?

TG: I only sought to be precise. I don’t think my prose tends in general to be “purple” – I’m not a big fan of the author showing off. That sort of prose comes between the reader and the nudity of what is being shown.

OP: How important was to you that Keith should be a musician? And why? I love that he thinks a lot about sounds, and the way he wishes to play just one infinite note stroke me as very genuine.

TG: I have played a lot of music myself. I played the piano. I once gave piano recitals, and also was in a band. Then I suffered nerve damage to my left hand. So this all came from experience. Keith’s injured hands… I felt I knew what that was like. And meanwhile, I usually write with headphones on, listening to something very loud…and then I have no memory of what it is I have heard.

OP: It seems to me as if Stainless is now like a time capsule of the nineties, not because is dated in any way but because it encapsulates perfectly a time and a place. I don’t know whether you’ll agree with that perception at all, but I’d like to know what were you seeing around you at the moment of writing, that led you or inspired you to create the ambiance that permeates the novel.

TG: I wrote it right after Brand New Cherry Flavor, which is more satirical, less emotional. It seemed like a continuation of that novel in some ways. Some of my friends became heroin addicts, so I suppose that influenced me, just because it was all around. I’ve scored drugs with more experienced junkies. Once I committed myself to the project and saw this as a milieu that I could live in, the goth kids and so on just fell into place out of all those I saw or knew. But I wasn’t trying to make a grand statement about the times. I was always, always, asking myself “Does this make sense?” And I was trying to really understand Justine, who is not a modern young woman. To that end I immersed myself in Georges Bernanos’ novel Diary of a Country Priest (and the film made of this by Robert Bresson), and I watched Bertrand Tavernier’s The Passion of Beatrice easily more than one hundred times. The last sixteen minutes of that film portrays a mysterious, perfect ritual that moved me every time, often to actual tears. And then I would write, after the close-up of her face when she is lost, she realizes she is forever damned.

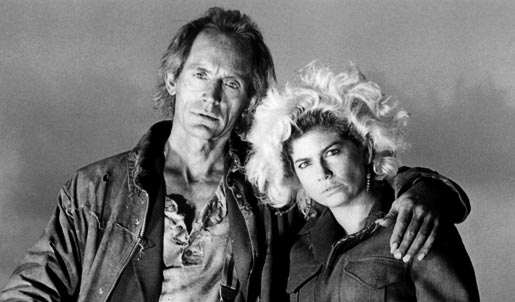

Lance Henriksen and Jennette Goldstein in Near Dark.

OP: If I’m not mistaken, you did sell the film rights for Stainless, but as far as I know, nothing came of that. Did Hollywood screw you as anybody else?

TG: Lise Raven, an independent filmmaker, wrote a treatment, and kept trying for several years. The big studios all kept saying they each had their own vampire film in development. Lise Raven – and my Hollywood agent, Lisa Callamaro, would say “But wait, this would be the ultimate, this gives you everything and anything you’ve ever thought you might get from the vampire mythos!” I still hope there might be a film, both because I hope such a film might be great – and because a film might bring more people to read the book. Sigourney Weaver and 20th Century Fox took an option on Brand New Cherry Flavor, which gave me more money – but would probably be a much more difficult film to make. Stainless is right there. Just use the dialog in the book. There’s no need for expensive CGI. Use unknowns and keep it simple and direct.

OP: Since we’re talking about film, name your three favorite vampire movies

TG: Near Dark; Count Yorga, Vampire; Bram Stoker’s Dracula (w/Gary Oldman).

- If you live in a country where Spotify is licensed, be sure to check this selection of tunes handpicked by Todd as the perfect soundtrack for Stainless.

Authors • Interviews

Es Pop Ediciones, Stainless, Todd Grimson Sin comentarios